The Spellbinding World of Owl Acoustics…

Posted by Acoustics First in Articles, Uncategorized on October 16, 2025

Today we thought we’d take a break from the usual Acoustics First blog topics and talk about owls and the fascinating way in which they experience acoustics. Owls possess some of the sharpest hearing in the animal kingdom. But what makes their hearing so exceptional and how does it differ from our own?

The secret lies in the unique structure of their faces and ears. Owls have flat, circular faces which gives them an incredible ability. Their facial discs, a set of specialized feathers arranged in a ring around their face, act like a natural sound collector, similar to a satellite dish picking up signals. These feathers are flexible, allowing them to adjust their position for optimal sound gathering. The sound they collect is then funneled into their ear openings located on the sides of their head. Imagine if we could move our ears to “zero in” on a particular sound!

Now, you might be wondering about those “ears” that stick up from an owl’s head. These aren’t actually ears at all! Those feathers are called plumicorns, and while they help with camouflage and communication between owls, they don’t contribute to hearing. The true ear openings are located on the sides of the owl’s head, much like humans. These openings are protected by a layer of feathers, and in some species, they even have movable flaps that can cover the ears. These flaps don’t interfere with hearing; they help reduce the sound of air turbulence when the owl is in flight.

What makes an owl’s hearing even more extraordinary is the position of its ear-holes. Unlike most animals, owl ear openings are asymmetrical, meaning one ear sits higher than the other. This unique design allows them to pinpoint sounds not only left or right, but also above or below. Thanks to this setup, owls can triangulate the source of a sound with incredible precision—sometimes within millimeters! This ability allows them to swoop down and catch prey they’ve never seen. The degree of asymmetry varies among owl species—some, like the Northern Saw-Whet, have a noticeable difference in ear placement, while others have more subtle variations. Either way, it’s an impressive adaptation!

Humans, like many other animals, have symmetrical ear-holes, making it more difficult for us to pinpoint whether a sound is coming from above, below or directly in front of us. This is why central clusters of speakers installed above a lectern effectively make the sound feel like it’s coming directly from the orator, not from the ceiling speakers.

Owls also have a “sound-location memory” that further enhances their hearing. When they hear a sound, their brains create a mental map of its location relative to the owl’s position. Special cells in their brain help process sounds from different directions, allowing them to track and locate the sound later.

Finally, like dogs, owls have a broader range of hearing than humans, and they can detect finer details within sounds. According to researchers, owls can hear sounds much faster than we can. While humans process sounds in increments of about 50 milliseconds, birds can discern sounds as short as 5ms. This means that where humans might hear a single note, owls may hear up to 10 distinct notes. Their auditory skills are truly out of this world—and it makes you wonder what we might be missing in our own world of sound!

Sabins, SAC, & NRC — a practical guide.

Posted by Acoustics First in Articles, HOW TO, Absorption on September 18, 2025

When optimizing a room’s acoustics, you’re often balancing how much sound is absorbed (loss) against how much bounces around (reverberation). Some common ways to describe absorption — sabins, SAC, and NRC — look different, but they’re closely related.

Sabins

A sabin is a direct measure of absorption: One sabin equals the sound-absorbing effect of one square foot of a perfectly absorbing surface (like an open window – sound goes out, but doesn’t come back.) In practice, manufacturers or labs will report a component’s equivalent absorption area in sabins at various frequencies. Sabins are additive: add the sabins of all items in a space to get the room’s total absorption for use in reverberation calculations.

SAC

Sound absorption coefficients (SAC) are used to simplify large square footage calculations. Each SAC itself is derived from the measured equivalent sabins of a test sample divided by the sample’s area. This allows you to multiply the square footage of a certain material by the SAC and it will tell you how many sabins it will absorb at a certain frequency. You may also see an average of all the SACs, or a subset of those values… a specific, often-used subset is the Noise Reduction Coefficient (NRC).

NRC and how it’s calculated

NRC (Noise Reduction Coefficient) is a number that represents a material’s average absorption performance at mid-to-high frequencies. It’s calculated by taking the arithmetic average of the material’s sound absorption coefficients (SACs) at 250 Hz, 500 Hz, 1000 Hz and 2000 Hz (per ASTM C423 or other standard test procedures). NRC is typically reported to the nearest 0.05 and runs from 0.00 (reflective) to 1.00 (very absorbent). Being an average, it isn’t the most accurate method, but it can give you a quick estimate which can be useful in the planning stages.

Practical Mathematic Relationship

- From measured data: SAC = measured sabins ÷ sample area.

- NRC is the average of SACs across four bands (250 Hz, 500 Hz, 1000 Hz and 2000 Hz).

- To convert NRC into a working absorption number for a planar surface:

sabins = NRC × area (ft²). - For discrete units (baffles, clouds): manufacturers often give sabins per unit, so total absorption is sabins per unit × number of units.

Why sabins for baffles and NRC for wall/ceiling panels?

Hanging devices like baffles are three-dimensional, exposed on multiple faces, and their effective absorption depends on orientation, spacing, and edge behavior. It’s more accurate and user-friendly to report their absorption as “# sabins per unit.” Flat-mounted wall or ceiling panels cover a known area and behave predictably per square foot, so SAC or an NRC (per ft²) is a convenient, normalized way to estimate absorption across a room.

Putting it into RT60 calculations

RT60 calculations depict the amount of time it takes for a sound to decay 60dB in a particular space with specific treatments. (60dB is roughly a 1000-fold reduction in sound pressure.) Reverberation-time formulas (like Sabine’s) use the room’s total absorption in sabins in the function. A basic average will use NRC × area for planar coverage and add sabins-per-unit for baffles. Sum everything up to get total sabins, then plug that into your RT calculation to estimate RT60.

If using feet your calculation is…

RT60 = 0.049 x Room Volume ÷ Total Sabins

If using metric your calculation is…

RT60 = 0.161 x Room Volume ÷ Total (Metric) Sabins

In summary:

NRC is an area-based average (for flat-coverage estimates); SAC is a sabins per square foot coefficient (for efficient absorption calculations using area); sabins per unit are direct, measured absorption values (better for discrete, hung, multi-faced items).

Similar, yet different: Angled QRD vs. Standard QRD

Posted by Acoustics First in Diffusion, Product Applications, Products on August 19, 2025

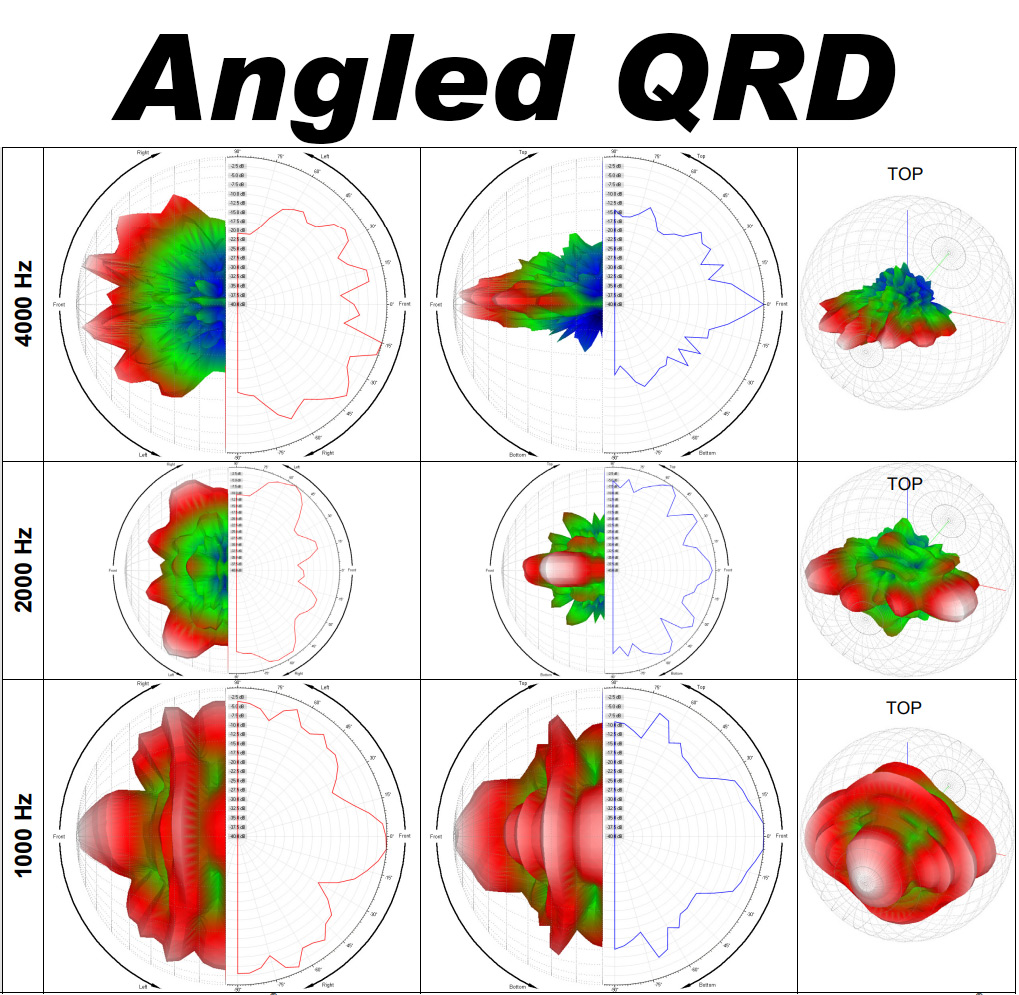

In this installment of “Similar, yet Different,” we explore the similarities and subtle differences between a classic, standard 1D QRD and a modern, angled 1D QRD. While being based on the same mathematic function for their design, there are a couple subtle differences in the performance of these devices.

Quick review. A Quadratic Residue Diffuser is based on a mathematic equation that states that the Well Depth is decided based on the square of the position of the cell and the remainder of when it is divided by a prime number. (We know it sounds really complex… but this is how the ratios of the wells are calculated to maintain a balance of magnitude across the face of the device.)

The equation looks like this:

Well Depth = (n² modulo p)

(Note: there will not be a quiz!)

As it was stated, both of the devices use the identical calculation when coming up with their wells… but there is one important change – the well bottoms are flat on the standard QRD and angled on the angled quadratic. This change makes this diffuser perform differently in 2 key ways:

- The Diffusion Pattern is wider on the angled QRD.

- There is a more subtle transition from one frequency to the next on the angled QRD.

When you look at the two sets of polar pattern above, you will notice that the Angled QRD has a wider pattern, as shown in the first-column, horizonal polar pattern (at 2000Hz especially), where the standard QRD is a more forward-focused pattern.

What does that mean in practice?

Both of these diffusers have a 1D pattern, but the flat bottoms of the standard QRD primarily use diffraction and incidence angle to widen the diffusion… the rest of the diffusion works on the principal of phase offset from the depth of the wells and the time of travel. The Angled QRD introduces an angle which means that one side of the well is deeper than another. This changes the reflection angle, time of travel, and, in turn, degrees of phase shift depending on where the sound strikes the inside of the well. This modification smooths the transition of phase from well to well – as the wells themselves have a range of phase change. This angle also causes the sound to be redirected toward the inner walls of the wells, causing it to change direction from the angle of incidence – widening the pattern further, changing the travel time, and basically bouncing sound around more.

There are some situations where the standard QRD‘s narrow pattern and well-defined transition frequencies may be preferable. In some practice rooms or larger listening spaces, there may be a need for the diffusion to be a little more directional, maybe to hit (or avoid) a certain position in the room. In these scenarios, the standard quadratic may be the recommended choice. In other spaces where you want the reflections to spread out more rapidly – maybe in smaller rooms or spaces where you need to get more coverage from ceiling reflections – then the angled quadratic may be more appropriate.

In closing, while these two devices have a nearly identical design, a small difference can have a big effect on the performance of the diffuser – and how you use them.

Don’t Knock the Knock: Acoustics and the Pursuit of the Perfect Watermelon

Posted by Acoustics First in HOW TO, Uncategorized on July 3, 2025

After being outside on a hot summer’s day, nothing quite hits the spot like a slice of a cool, crisp, sweet watermelon. Unfortunately, not every watermelon is the same, and everyone has different methods for selecting the best ones.

There are number of visual clues that one can rely on to help identify a good watermelon. A large, yellow field spot on the bottom indicates that the watermelon was on the vine longer and is probably sweeter. Also, the coloring of a “ripe” melon will have strong, consistent stripe pattern; dull dark green stripes alternating with light yellow/pale stripes.

However, even when I followed these visual tells, I would often cut into my purchase only to be dismayed by a Styrofoam-like, flavorless inside or an over-ripened, mushy mess.

This melon melancholy haunted me until a few years back when I saw a middle-aged woman kneeling on the concrete floor of the supermarket with 5 watermelons circling her. I watched as she bent over and carefully knocked on each one, listening and nodding her head like she was holding a séance with the “other side” of the produce aisle. She repeated this process, rearranging the melons in front of her, until she picked up “the one” and put it in her cart, returning the other watermelons to the display bin.

I greeted the woman, trying not to startle her, and admitted that I often struggled to pick out watermelons. Clearly, she knew what she was doing and I was curious if she might share her system with me.

She kindly told me that she was listening for a “hollow” sound, that was full, but not too deep in pitch. I told her that I had heard that this “knock” test is a good way to judge the water content, but I never had much luck. She said that people will make the mistake of holding onto the melon when knocking, which quickly dampens the sound, so you can’t hear much of a tonal difference between melons (like palming the string of a guitar will change its sound to a shorter, more percussive, note).

Her strategy is to pick out 4-6 similar sized melons that have a large, yellowish sugar spot and strong striping, then sets each down so the only point of contact is with the hard floor. Without external dampeners, the melon can really “sing” when knocked, telling her how far along the fruit is. Too deep of a sound and the fruit is over-ripe/mushy, too high-pitch (or not hollow at all) and the watermelon is not ripe enough. She organizes the melons from lowest to highest in pitch and she simply selects from the middle melons to find one or two that are “just right”.

She said that this ritual, as ridiculous as it might appear to other shoppers, is the best way to guarantee a good watermelon and it’s worked for me ever since; so, don’t knock the knock!

Eight very different 2′ x 2′ sound diffusers.

Posted by Acoustics First in Diffusion, Product Applications, Products, Recording Facilities on June 30, 2025

Acoustics First® has maximized the idea of adaptable designs. One of the most common modular architectural elements is the 2′ x 2′ ceiling grid. While standard, fiber ceiling tiles have their uses, specialized acoustic environments require higher-performing materials – for both absorption and diffusion. While Acoustics First® excels with its Sonora® and Cloudscape® Ceiling tiles, today we are going to focus on the wide range of 2’x 2′ diffusers that have been developed over the several decades.

Sound diffusers in a 2′ x 2′ format have several advantages, other than just being placed in a ceiling grid to help diffuse the ceiling. They integrate well on walls and in arrays, where they can help break up large flat surfaces and help minimize flutter and standing waves from parallel surfaces. While they provide many different aesthetic options, there are also many different functional types of diffusers available in this form-factor to address different acoustic issues, from flutter, bass issues, targeted frequency absorption, and geometric scattering. Let’s look at some of these devices and their uses.

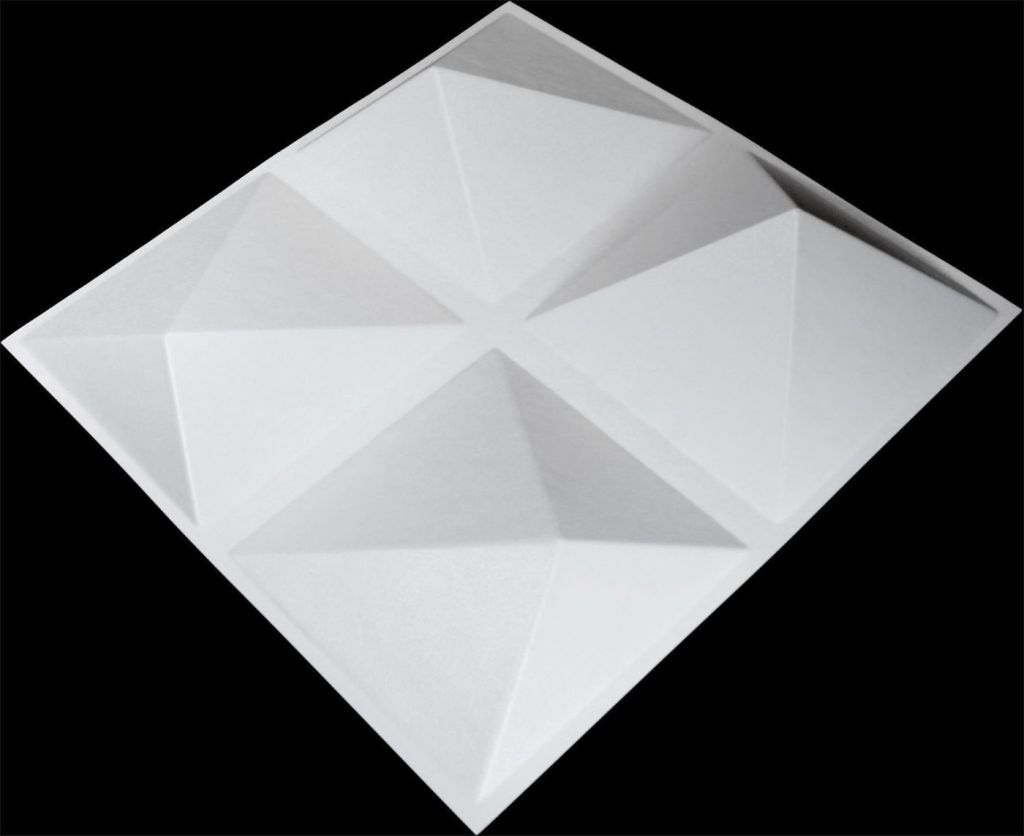

Geometric Diffusers.

Geometric diffusers have been around a long time. These devices break up large flat surfaces and redirect or “scatter” those reflections in different directions. They work great in environments where you need to redirect acoustic energy in a predictable way, and redistribute a specular reflection over a wider area. In a 2′ x 2′ size, you can also get a fair amount of bass absorption, due to the large cavity behind the geometric shapes creating a space that can be stuffed with absorbent material to tune it.

Quadratic/Mathematic Diffusers

Mathematic diffusers are devices that use specific calculations to design their size, shape, and structures to effect their performance. A common type is called the Quadratic Residue Diffuser (sometimes called a Schroeder Diffuser, after its pioneering inventor, Manfred Schroeder). This type uses a Quadratic Residue Sequence that optimizes uniform sound diffusion at specific design frequencies. There are different ways to implement these designs, but two common designations are based on their diffusion patters – 1D or 2D. A 1D Quadratic diffuser mostly spreads energy in one plane, and a 2D provides a hemispheric pattern.

Organic Diffusers.

Organic diffusers are a variation on the classic mathematic diffusers which use different mathematic functions to optimize the diffusion further by creating a smooth transition. Once such method is called Bicubic Interpolation. Instead of having the math restricted to having blocks at certain heights, the interpolation bridges these heights using a function that provides a smooth transition to the next target height. This transition creates unlimited resolution in the frequencies within it’s functional range, providing expanded uniformity throughout its range, and increasing its capabilities. As different frequencies are affected differently depending on their wavelength – the organic diffusers have no hard edges to define their pattern and look differently to different frequencies and energy from varied sources.

These diffusers all have the ability to be used in different types of installations for different reasons. Many of these diffusers are mixed and matched in the same room. You will see these on the walls or ceiling, and placed in different locations. There are rooms with Double-Duty diffusers for low frequency control, Model C for Mids, and Model F for flutter, while other rooms may have Aeolians™ on the rear wall and Model C’s and Model F’s to control the ceiling.

Keep in mind, these aren’t even all the diffusers we have available, these are just the ones specific to the 2′ x 2′ format. The Aeolian™ has a 1′ x 1′ version called the Aeolian™ Mini. There are flat panel diffusers that are hybrid absorbers and diffuser like the HiPer Panel® and the HiPer Panel® Impact. There are even large format versions of the Double Duty™ diffuser, Pyramidal, and even the Quadratic Diffuser.

For more info about these diffusers, read some of our, “Similar, Yet Different Series,” where we go into more detail about our products… and how some of these are similar, yet different!”

If you have any questions as to which products you need to optimize your space, reach out to Acoustics First® and we can help you find which products will be best for your application. Remember that Acoustics First’s® full line of sound diffusers are all made in the USA, with many available in stock for quick shipping.

You must be logged in to post a comment.