Acoustics First

This user hasn't shared any biographical information

Homepage: http://acousticsfirst.info

Joint ASA/ASJ Meeting – 2025 Recap

Posted in Press Release, Uncategorized on January 23, 2026

The joint meeting of the Acoustical Society of America (ASA) and the Acoustical Society of Japan (ASJ), held in Honolulu in December 2025, was a welcoming gathering for the international acoustics community. This joint congress happens only once every ten years, making it a rare opportunity for researchers, consultants, and students from both societies to come together, reconnect, and exchange ideas. Hosting the meeting in Hawaiʻi—literally and figuratively a bridge between the two countries—added to the collaborative and relaxed atmosphere.

Across the week, a wide range of ASA and ASJ technical committees organized sessions that showcased the diversity of acoustics research and practice. These included:

- Architectural Acoustics

- Noise

- Physical Acoustics

- Psychological and Physiological Acoustics

- Speech Communication

- Musical Acoustics

- Computational Acoustics

- Engineering Acoustics

- Education in Acoustics

- Structural Acoustics and Vibration

- Underwater Acoustics

- Signal Processing in Acoustics

- Biomedical Acoustics

- Animal Bioacoustics

- Acoustical Oceanography

Together, these sessions reflected the breadth of the field—from fundamental physics to human perception, from engineered systems to the natural environment.

One such session was organized by the Architectural Acoustics Technical Committee and focused on the Advances in Absorption Measurement and Design. Presentations explored how these materials are evaluated in the lab, how they are specified and integrated into buildings, and how they ultimately shape the acoustic experience of everyday spaces. This session was co-chaired by Jim DeGrandis (Acoustics First Corporation) & Daniel Robinson (Sublime) from the ASA, as well as Toshiki Hanyu (Nihon University) and Tetsuya Sakuma (The University of Tokyo) from the ASJ.

A highlight of the session was a three-part breakdown of a developing Japanese acoustics standard for general spaces—such as lobbies, sporting facilities, and multipurpose rooms. The proposed standard is being informed by the well-established German DIN 18041 room acoustics standard, with thoughtful adaptations for Japanese building practices and cultural expectations. The presentation sparked lively and friendly discussion, illustrating how international collaboration can help refine tools and standards that benefit practitioners worldwide.

Overall, the session captured the spirit of the once-a-decade ASA–ASJ meeting: technically rigorous, openly collaborative, and genuinely enjoyable.

End-of-Year Warehouse SALE 2025!

Posted in Absorption, Diffusion, Press Release, Products on December 23, 2025

It’s that time again! Time to do The End-of-Year cleanout of overstock, B-Stock, etc! Help us clean house!

Free Ground Shipping to the lower 48 states included on warehouse sale items – Available until January 31st… or while supplies last!

Aeolian™ Sound Diffusers – B-Stock

These Aeolian™ Diffusers have minor imperfections due to the batch of plastic having small orange specs in it. Barely noticeable, and easily paintable.

Quantity at time of writing – 102

Original Price $175 per unit – Sale price $87.50 per unit!

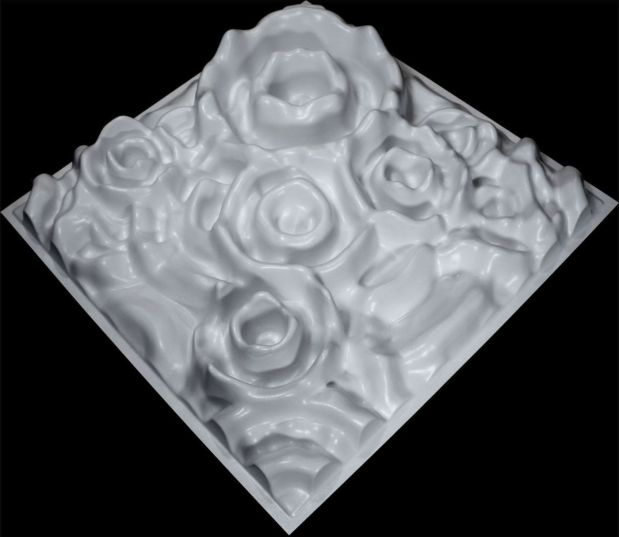

ArtDiffusor® Model D Sound Diffusers – Overstock

These ArtDiffusor® Model D Diffusers are A-Grade Stock – they are simply overstock items!

Quantity at time of writing – 96

Original Price $175 per unit – Sale price $87.50 per unit!

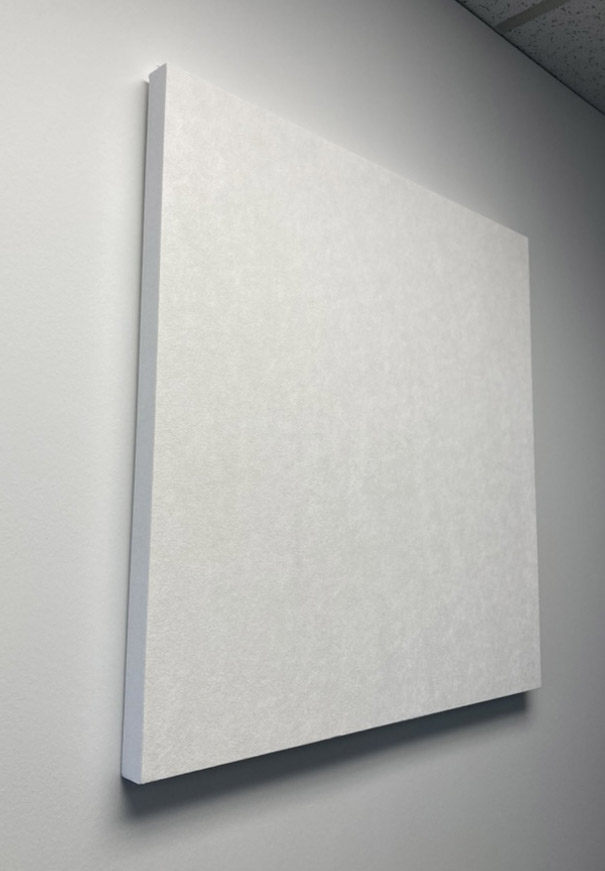

2’x2’x1″ Tone Tiles – Overstock

These 2’x2’x1″ ToneTiles are A-Grade Stock – they are simply overstock items!

Quantity at time of writing – 60

Original Price $70 per unit – Sale price $35.00 per unit!

2’x2′ Cloudscape Ceiling Tiles – Tile Backed – Customer Return

These Cloudscape Ceiling Tiles with Fog Pattern are a customer return – Listed as B-Stock. They are mounted to a ceiling tile backer for use in a drop ceiling grid.

Quantity at time of writing – 66

Original Price $60 per unit – Sale price $30.00 per unit!

Contact Acoustics First today at 888-765-2900 or reach out to info@acousticsfirst.com to inquire about these deals – but don’t wait… once they are gone, that’s it!

Big vs. Bigger: 2′ vs 4′ Acoustic Diffusers

Posted in Diffusion, Product Applications, Products on December 16, 2025

A couple common form factors in acoustics are based on building material sizes. Ceiling grids are a common place to install acoustic devices, and you will find that many are built to either work in a 2’x2′, 2’x4′, or 4’x4′ ceiling grid installation. This makes sense, but did you know that these devices also perform differently in some cases due to their dimensions? This is especially true with acoustic diffusers.

When you’re tuning a room—whether it’s a studio, theater, rehearsal space, or even a high-end listening room—acoustic diffusers are one of those rare tools that improve clarity without taking the life out of the space. Designs like the Double Duty Diffuser, Pyramidal Diffusers, and Quadratic Diffusers all share that same mission: redistribute sound energy so your room feels open, natural, and honest.

But while they may look similar in concept, their size changes the game. A 2’x2′ panel and a 4’x4′ panel both diffuse sound, but their effect—especially in the low-frequency and low-mid ranges—can be very different.

2’x2′ Diffusers — Compact Control

2’x2′ units are the most modular diffusers in the lineup. Their smaller footprint makes them ideal for:

- Breaking up mid and high-frequency reflections

- Treating small and medium rooms

- Sitting comfortably in grid ceilings or tight wall spaces

Because of their size, 2’x2′ diffusers don’t interact as much with the low-frequency energy in a room. Bass waves—being physically large—tend to wrap around smaller objects. The result? Excellent clarity improvements in the mids and highs, with a very predictable diffusion performance. The Double Duty Diffuser and Pyramidal diffusers have been a standard in breaking up planar surfaces for decades. While their diffusion in low frequencies is limited at this size, the air cavities do help control some upper bass frequencies through absorption.

The tuned mid frequency effects of the 2’x2′ quadratic, and the smooth performance of the Double Duty or Pyramidal diffuser are perfect for control rooms, edit rooms, drum booths, and anywhere you want accuracy without sacrificing sparkle.

4’x4′ Diffusers — Where Diffusion meets Bass Control

Now we get to the big ones.

A 4’x4′ diffuser is similar in concept to its smaller relatives, but the scale moves it into a different acoustic category. At this size, diffusers begin to influence longer wavelengths, which opens the door to something smaller diffusers often struggle with…

Low-frequency interaction

Large diffusers present enough depth, volume, and surface area to affect the bass spectrum. The extra size creates cavities which are tuned to reduce bass, and they have surfaces large enough to redirect those lower frequencies.

- Break up standing waves in the low-mid range

- Reduce modes and nodes common in rectangular rooms

- Add a sense of openness to the bass field

- Prevent buildup behind listening positions

In other words: same diffuser concept, very different low-end behavior.

Wide-area coverage

A single 4’x4′ panel can modify a huge portion of a wall, creating an even, spacious character that feels less like “treatment” and more like a room that’s naturally well-behaved.

These panels shine in larger studios, live rooms, and worship spaces—anywhere you need diffusion that reaches deeper into the frequency spectrum – and can break-up large, flat, specular surface reflections, which are responsible for flutter, echoes, bass buildup, and long reverb times.

Which do you need?

There are two main factors in the decision: space and performance requirements. In certain environments, it’s impractical or impossible to install large 4’x4′ or larger diffusers; It also may not be the best solution – even if it may appear to be on paper. While a single, large barrel diffuser may appear ideal, you may not have enough physical space to allow the diffusion to develop – where several smaller diffusers would be the better solution.

In short, your physical space and acoustic conditions will dictate which size elements will give you the most benefit in your environment.

You say “Diffuser,” I say “Diffusor”

Posted in Diffusion, Q&A, Uncategorized on November 11, 2025

If you’ve spent any time around acoustic treatment—especially sound diffusion—you’ve probably noticed something odd: sometimes the product is called a “diffuser“, and other times it’s a “diffusor“. For newcomers, this can feel like a secret code or a subtle technical distinction – But the truth is much simpler.

Many trace the dual spelling back to Manfred Schroeder, the German physicist who developed the mathematically designed Quadratic Residue Diffusor (QRD).

In German, the word is spelled “Diffusor.” When Schroeder’s work entered the academic world, the spelling likely came with it.

Because his research became foundational in architectural acoustics, the German spelling spread through physics papers, textbooks, and graduate-level acoustics programs. Over time, “diffusor” became a common spelling when discussing mathematical or Schroeder-style diffusors specifically.

As manufacturers began producing these mathematically derived designs—like the ArtDiffusor® line from Acoustics First® (and many other early products)—they retained the “diffusor” spelling as a nod to the academic and scientific origins.

Before long, the industry ended up with two spellings that referred to the same thing:

- Diffuser – the standard English spelling

- Diffusor – the academically inherited, German-influenced spelling tied to Schroeder’s work

Both spellings appear throughout the professional audio world, and both are correct.

Is There Any Practical Difference?

No. None. Zero.

There is no technical difference between a “diffuser” and a “diffusor.” They both refer to devices used to redistribute sound energy and improve the acoustic quality of a space through accelerating the development of sound field diffusion. The spelling variation is purely linguistic.

Think of it like “colour” vs. “color” or “flavour” vs. “flavor.” British English keeps the “u,” American English drops it. (However, if you ask a Brit, they’ll tell you Americans are obviously spelling it wrong.)

The “diffusor/diffuser” split works the same way—just with a German twist.

So Which Should You Use?

Use whichever feels natural or matches the context you’re writing in. Many engineers and academics use “diffusor” when referring to Schroeder-type or other mathematical designs, simply out of tradition. Others stick with the standard English “diffuser.”

Tomato. Tom-ah-to.

The Spellbinding World of Owl Acoustics…

Posted in Articles, Uncategorized on October 16, 2025

Today we thought we’d take a break from the usual Acoustics First blog topics and talk about owls and the fascinating way in which they experience acoustics. Owls possess some of the sharpest hearing in the animal kingdom. But what makes their hearing so exceptional and how does it differ from our own?

The secret lies in the unique structure of their faces and ears. Owls have flat, circular faces which gives them an incredible ability. Their facial discs, a set of specialized feathers arranged in a ring around their face, act like a natural sound collector, similar to a satellite dish picking up signals. These feathers are flexible, allowing them to adjust their position for optimal sound gathering. The sound they collect is then funneled into their ear openings located on the sides of their head. Imagine if we could move our ears to “zero in” on a particular sound!

Now, you might be wondering about those “ears” that stick up from an owl’s head. These aren’t actually ears at all! Those feathers are called plumicorns, and while they help with camouflage and communication between owls, they don’t contribute to hearing. The true ear openings are located on the sides of the owl’s head, much like humans. These openings are protected by a layer of feathers, and in some species, they even have movable flaps that can cover the ears. These flaps don’t interfere with hearing; they help reduce the sound of air turbulence when the owl is in flight.

What makes an owl’s hearing even more extraordinary is the position of its ear-holes. Unlike most animals, owl ear openings are asymmetrical, meaning one ear sits higher than the other. This unique design allows them to pinpoint sounds not only left or right, but also above or below. Thanks to this setup, owls can triangulate the source of a sound with incredible precision—sometimes within millimeters! This ability allows them to swoop down and catch prey they’ve never seen. The degree of asymmetry varies among owl species—some, like the Northern Saw-Whet, have a noticeable difference in ear placement, while others have more subtle variations. Either way, it’s an impressive adaptation!

Humans, like many other animals, have symmetrical ear-holes, making it more difficult for us to pinpoint whether a sound is coming from above, below or directly in front of us. This is why central clusters of speakers installed above a lectern effectively make the sound feel like it’s coming directly from the orator, not from the ceiling speakers.

Owls also have a “sound-location memory” that further enhances their hearing. When they hear a sound, their brains create a mental map of its location relative to the owl’s position. Special cells in their brain help process sounds from different directions, allowing them to track and locate the sound later.

Finally, like dogs, owls have a broader range of hearing than humans, and they can detect finer details within sounds. According to researchers, owls can hear sounds much faster than we can. While humans process sounds in increments of about 50 milliseconds, birds can discern sounds as short as 5ms. This means that where humans might hear a single note, owls may hear up to 10 distinct notes. Their auditory skills are truly out of this world—and it makes you wonder what we might be missing in our own world of sound!

You must be logged in to post a comment.